From Denying to the Grave

From Denying to the Grave: Why We Ignore the Facts That Will Save Us

by Sara E. Gorman, Jack M. Gorman, M.d., Jack M. Gorman, Oxford University Press

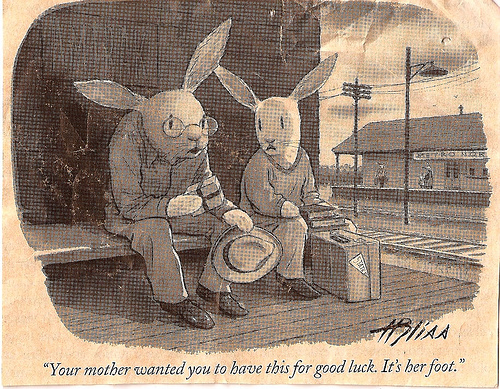

Rabbit Feet and Other Strange Beliefs

Many definitions of superstition involve the notion that superstition is established by a false assignment of cause and effect. Superstition is an extremely powerful human inclination that perfectly fits the notion of filling the ignorance gap. We cannot know why many things around us happen, so we invent reasons or ways to try to control occurrences and we assign causes to nonrelated incidents that may have occurred alongside an event. We all know how this works, of course, and we are all guilty of engaging in superstition, even if we do not consider ourselves particularly superstitious people. We might re-wear clothing that we thought brought us good luck at a recent successful interview or eat the same cereal before a test that we ate before another test on which we performed well. These are examples of superstitious behaviour. Many psychologists, medical researchers, and philosophers have framed superstition as a cognitive error. Yet in his 1998 book Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time, Michael Shermer challenges the notion that superstition is altogether irrational. Shermer effectively asks why superstition would be so pervasive if it were a completely irrational, harmful behaviour. Shermer hypothesises that in making causal associations, humans confront the option to deal with one of two types of errors that are described in classic statistical texts: Type I errors involve accepting something that is not true, and Type II errors involve rejecting something that is true. Shermer proposes that in situations in which committing a Type II error would be detrimental to survival, natural selection favours strategies that involve committing Type I errors. Hence superstitions and false beliefs about cause and effect arise. This is precisely the argument we made earlier with our example about avoiding orange and black after an attack by an orange-and-black animal: erring on the side of caution and believing something that may not be true is more beneficial than potentially rejecting something that may be true—for example, that everything orange and black is a threat.”

Well, that explains a lot.

May God’s love save you from all this scientistic claptrap.

LikeLiked by 4 people

You monster! Monsterrrrrrrrrrrr! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was not explained well. The argument goes like this: if you see the tall grass wavering, is it the wind or a tiger stalking you? If you think it is a tiger and avoid that area and you are wrong, there is no penalty. If you think, it is the wind and are wrong, the penalty could be quite severe. You are better off to believe an invisible animal is there and taking precautions whether you are right or wrong. This is how the feeling that invisible animals (gods, etc.) exist is based in sound decision making practices.

LikeLiked by 6 people

That is indeed a much better example.

What importance do you think the conditional pseudo-proof (pseudo conditional-proof ?) has in the process? It seems to be the go to rhetorical device of the Trump/Le Pen crowd.

LikeLike

You guys should know that Jurassic Park/World movies are fiction, do you?! Tall grass, raptors, Indominus Rex, In Nomine Patris, Amen 🤓😵👾🖖

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is why I disagree with those “militant atheists” who claim that we should not believe anything without evidence and preach the “burden of proof” principle as universal, saying that those who make statements must provide the evidence rather than asking others to disprove them. Indeed, it’s all a matter of which of the two errors is safer. A bomb threat is taken seriously until proven false, not the other way around.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I understand that conceptually, but doesn’t it lead to an impossible mathematical problem? Or at least one where we still must dismiss specific god theories?

LikeLike

Theologies are not accepted or rejected based on any experimental results.

LikeLike

Like Marlon Brando once said to Jimmy, the boy who lived next door to him, “Jimmy, I wasn’t a superstitious man until I heard about this rabbi dude who rose from the dead 3 days after he was crucified. That’s a story that simply must be true because who in fuck’s name would make something like that up. HEY! don’t walk under that ladder you idiot! You’ll have bad luck for decades!”

LikeLiked by 4 people

😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s hardwired for a very good reason. It was once very, very useful.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Now explain how and why that applies to whole political movements? 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Because its easier, the path of less resistance. Remember a while ago you posted about a study that found that the more we lie, and the more we are exposed to the lies of others, the easier it all becomes?

LikeLiked by 2 people

It’s simple physiology. Remember the Pavlov’s experiment with the dog? When food follows a bell for a few times, the dog starts to salivate on the bell even if there is no food. Is it rational or irrational? I don’t think the dog rationalizes much before salivating. Therefore, this behavior is irrational. On the other hand, it is certainly, understandable and explainable and, therefore, rational.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Have a look at this study, very interesting- particularly the section on pigeons:

“In one of his experiments on operant conditioning, Skinner presented the pigeons with food at random intervals and noted that they still displayed ritualized behaviours that he interpreted as superstitious, i.e. the pigeon was behaving as though its actions were causing the food to arrive. However, these behaviours were later reinterpreted as behaviours that improve foraging efficacy (analogous to salivation in Pavlov’s dogs), which suggests that the pigeons’ behaviour does not correspond to Skinner’s intended meaning of superstition (Staddon & Simmelhag 1971; Timberlake & Lucas 1985; Moore 2004). Nevertheless, Skinner’s early account is notable in two respects. First, it recognized the possibility of superstition occurring outside the human realm. Second, and linked to this, Skinner emphasized the behavioural aspect of superstition: ‘The bird behaves as if there were a causal relation between its behavior and the presentation of food, although such a relation is lacking.’ (Skinner 1948). That is, he focused on there being an incorrect response to a stimulus (behavioural outcome), rather than the conscious abstract representation of cause and effect (psychological relationship), with which human superstitions are often associated.”

LikeLiked by 3 people

It’s funny how someone’s motives are sometimes totally misinterpreted or the “benefits” of one’s actions may be totally not what we expect. There is a joke about two panhandlers sitting next to each other in a street in Ukraine. One holds a Ukrainian flag, the other one holds a Russian flag. The hat of the one holding the Ukrainian flag is full, the hat of the one holding the Russian flag is empty. One passer-by says to the one holding the Russian flag: “Maybe you should hold a Ukrainian flag instead”. The panhandler turns to his fellow and says: “Listen, Moshe, this putz will teach us how to do gesheft.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

🤣

LikeLike

The concept of intermittent rewards is behind the success of slot machines and works just as well for pigeons as it does for humans. If you don’t know exactly why a reward happens, err on the side of safety and keep doing whatever seems to work.

Extrapolate this out to religion and you have a barren woman praying for a child in front of statue XX. Nothing happens for 10 years but then, Lo…she becomes pregnant. Ergo, her prayers must have been answered by that one, particular statue.

Voters pray for a politician who cares about /them/ and doesn’t bullshit like all the other politicians. Lo…Trump appears and starts telling the disaffected voters what they want to hear whilst ALSO hanging shit on other, ‘normal’ politicians. If he does one then he must do the other, right? There is a logic there, of sorts, it’s just not logical logic. And thanks to intermittent rewards, keeps them pecking that button labelled ‘Trump is my Saviour’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, okay – good timing. We recently returned from AUS where in the Blue Mountains we visited the Aborinal Center for arts – a tiny tourist trap that contained, to my horror, kangaroo feet on keychains. I once had a rabbit’s foot and rubbed its fur until it had no more. But that was less from superstition than from loving its softness. I always wondered why someone would cut off the feet of these shy creatures.

The other thing that this brings up is how long I avoided stepping on cracks in the sidewalk, even though I knew that doing so would not break my mother’s back. Then I moved away from sidewalks and cities and that broke that compulsive habit. Gosh, humans!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

When I was little I stepped on every crack I could find- never worked

LikeLiked by 3 people

Haha, you devil.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By the way, Type I error is rejecting a true hypothesis and Type II error is accepting a false one – the opposite to what you quoted.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Isn’t it ironic?

LikeLike

I’ve been wondering about that. At first I thought the author might mean that by rejecting a true hypothesis one was accepting something that wasn’t true; but now I think it must have been a mix up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Erroneously rejecting or accepting a reasonable hypothesis is not so bad. But sometimes one would wonder where people come up with some ideas.

Sorry for making too many comments here, but this post hits close to home for me since my job is statistical quality control and I happen to be interested in epistemological issues.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s actually very nice to know there are more people interested in these things 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person